TEXTS

^ MEMOS FROM JULIAN T. ^

WHY I DO WHAT I DO

Why I do what I do can be summarized into three principal explanatory categories:

The realistic reasons:

The act of creating things that are modeled after personal tastes, that incorporate personal experiences and that reflect your own mental, physical and energetic capacities (sometimes with surprisingly positive results, sometimes with disappointing results) is both a fundamental human need and one of the greatest pleasures in life. When I was still in high-school, I discovered that making art was an easily available means of regularly exercising my creative urge and satisfying the pleasure begot from a focused and sustained effort towards a self-defined end product without too many dependencies on the outside world. In what other field is it possible to empower yourself to execute a set of actions by which you can realize an envisaged goal without the consent, support and recognition of others and without having necessarily achieved anything prior to beginning your work? The beauty in art is that you can explore the depths of it both intellectually and practically at any and every moment in time.

In high school I started dedicating large portions of my week to making art. Why am I still doing what I did over ten years ago? The simplest and most truthful answer is that I built up a certain momentum throughout high-school, university and later on which has made it difficult to stop, especially because my habits and the environment in which I live has been set up towards this activity. It obviously takes a certain amount of energy and motivation to make new works, but it takes more energy and creativity to change your path than it does to stay on the same one. It is my assumption that until and unless something dramatic changes in my capabilities to manage the world around me and make things happen in a bigger way, I will continue making paintings because it is in this field that I have the least dissonance and the most focus and control.

Although its exact origins are uncertain, the following quote is frequently attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Sow a thought and you reap an action; sow an act and you reap a habit; sow a habit and you reap a character; sow a character and you reap a destiny.” I believe it is of relevance with regards to the realistic reasons for which I have pursued the business of making paintings.

The emotional reasons:

It is my opinion and belief that there is a symmetrical correspondence between the aesthetic dimension of man-made material products and the respective emotional, intellectual and spiritual states of being which are required to dream them up and give life to their physical form.

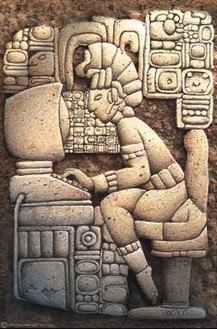

When I look at a work of art that I consider beautiful or appealing, several things happen. First, I am struck by its form, colour, composition. Then I become curious about the subject matter and the theory, idea or experience that was the impetus for creating the work. I ask myself what the social climate and economic conditions of the artist must have looked like in order to make this work of art a possibility, especially when I lay eyes upon works of exceptional scale (e.g. Werner Tuebke's Battle of Frankenhausen / Frank Stella's monumental maximalist works). Finally I ask myself what the internal climate of the artist(s) must have been in order to achieve the level of focus, dedication, motivation, perseverance and inspiration that is required to execute works of intense labour and exceptional craftsmanship (when looking at historical works by the Egyptians, Assyrians or Sumerians in the British Museum for example). After seeing works that inspire these thoughts and give rise to these questions, my desire to know the answers arises. Ultimately, it is this desire to know, from the inside out, what makes a great work of art possible, that is the driving force behind stretching up new canvases and getting out the paintbrushes.

The motivational reasons:

When I was very young it seemed strange to me that people relied on others in order to give them work. The business of working towards getting a job looked incredibly unappealing. Work to me was something that you would do because it was necessary, regardless of what kinds of rewards it might reap.

In most subjects there was always a factually right and wrong answer that you had to arrive at in order to be awarded high points. Personally, I never found any satisfaction in being awarded a high score for arriving at an answer that was 'right' and in so many cases, preformulated.

I was drawn to art at school because it was the only subject that did not impose any boundaries on my activity, prescribe any solutions or describe any particular method. In the art department, there were no restrictions on scale, on medium, on ideas or on anything else. The only problems that had to be solved were the ones you considered worthy of finding a solution to. And how you investigated your problem was entirely up to you. The only fundamental requirement to make the subject worthwhile was a deep sense of involvement in the types of solutions you were exploring. All the boundaries were self-imposed and this, in my perception, was a great way of exploring what the self was capable of.

As time went on and my exposure to art became wider, during my university years and through my travels, the sensations I would have in front of inspiring works of art stirred within me a desire for these works. I started painting on larger and larger scales because by experience it was the larger scale works that kept me fixed and mesmerized. I wanted to own the experience of a great painting or a great work of art and the only way to do this, unless you have the resources to purchase a wonderful work, is to make the work yourself.

© Julian Tschollar 2020

Thoughts on art

What's the goal?